I just finished this intense personal account of the 1996 Mt. Everest disaster. More than half of the book is primarily exposition and background information on the sport of mountaineering and on the individuals involved. Then once they've reached 8,000 meters (approx. 26,000 ft) and things start getting dicey with the oncoming gale, the books starts getting seriously tense and I couldn't put it down. While, the book is engrossing and truly an important warning for any inexperienced climber harboring romantic notions of reaching the roof of the world, this should serve as a sobering realization that Mt. Everest (Sagarmatha) is no small feat that relies not merely on technical skill and experience but also interminable will, self-discipline (to turn back around at the agreed-upon time even within a stone's throw of the summit), timing, and sheer luck.

I'm very grateful that Krakauer summoned the courage and resolve to write this harrowing personal account of the tragedy, but at the same time I can't help but agree with some of the criticism by the relatives of the deceased. At many times throughout the tale, Krakauer seemed to heavily criticize certain individuals or even groups of people who he felt directly contributed to the disaster. As I wasn't there I cannot judge the veracity of these allegations but they just rub me the wrong way.

Scott Fischer's sister, Lisa Fischer-Luckenback wrote:

What I am reading is YOUR OWN ego frantically struggling to make sense out of what happened. NO amount of your analyzing, criticizing, judging, or hypothesizing will bring the peace you are looking for. There are no answers. No one is at fault. No one is to blame. Everyone was doing their best at the given time under the given circumstances.

No one intended harm for one another. No one wanted to die.

What did shock me was how he described how callous some individuals were. For instance, the Japanese team who apparently saw the dying Ladakhis on the trail coming up from the Tibetan side of the mountain and merely ignored them without offering any assistance whatsoever. Then when interviewed about it, their (Hanada and Shigekawa) only response was, "We didn't know them. No, we didn't give them any water. We didn't talk to them. They had severe high-altitude sickness. They looked as if they were dangerous."

"Shigekawa explained, 'We were too tired to help. Above 8,000 meters is not a place where people can afford morality.' Turning their back on Smanla and Morup, the Japanese team resumed their ascent, passed the prayer flags and pitons left by the Ladakhis at 28,550 feet, and—in an astonishing display of tenacity— reached the summit at 11:45 A.M. in a screaming gale."

This passage made me take pause and I had to put down the book for a minute and get something to drink since I could not comprehend putting the dubious goal of reaching the summit over helping fellow human beings on the brink of death.

Having lived for a period of time in Taiwan myself it was also disheartening to hear of the poor actions and behaviors of the Taiwanese team, which was apparently universally panned and derided by the other groups. First for their incompetence in mountaineering and for their debacle on Mt. McKinley in Alaska where they placed the lives of others in danger. Then, this time on Mt. Everest, when one of their Taiwanese team members fell to his death while trying to evacuate his bowels, the team leader, 'Makalu' Gau, just replied, "O.K." on the radio and continued to make his ascent to the summit. (He explains his questionable actions and attitude in "Frontline: Storm Over Everest," but I'm wondering if this was just rationalization ex post facto.)

Of course, this book isn't entirely a chronicle about the foibles and frailties of man, but also about the triumph and heroism of common people. Stuart Hutchinson and Neal Beidelman stepped up when others collapsed due to hypoxia, hypothermia, severe altitude sickness (HAPE, HACE, etc.) and/or severe fatigue. Also, Rob Hall died almost entirely due to the responsibility he felt as leader of the expedition. He stayed up on the summit because Hansen could not budge without bottled oxygen. He could have easily left him and gone down to base camp but heroically and obdurately, he refused to leave him and as a result died due to exposure.

I think this message from a Sherpa hits the message home:

I am a Sherpa orphan. My father was killed in the Khumbu Icefall while load-ferrying for an expedition in the late sixties. My mother died just below Pheriche when her heart gave out under the weight of the load she was carrying for another expedition in 1970. Three of my siblings died from various causes, my sister and I were sent to foster homes in Europe and the U.S.

I never have gone back to my homeland because I feel it is cursed. My ancestors arrived in the Solo-Khumbu region fleeing from persecution in the lowlands. There they found sanctuary in the shadow of "Sagarmathaji," "mother goddess of the earth." In return they were expected to protect that goddesses' sanctuary from outsiders.

But my people went the other way. They helped outsiders find their way into the sanctuary and violate every limb of her body by standing on top of her, crowing in victory, and dirtying and polluting her bosom. Some of them have had to sacrifice themselves, others escaped through the skin of their teeth, or offered other lives in lieu. . . .

So I believe that even the Sherpas are to blame for the tragedy of 1996 on "Sagarmatha." I have no regrets of not going back, for I know the people of the area are doomed, and so are those rich, arrogant outsiders who feel they can conquer the world. Remember the Titanic. Even the unsinkable sank, and what are foolish mortals like Weather, Pittman, Fischer, Lopsang, Tenzing, Messner, Bonington in the face of the "Mother Goddess." As such I have vowed never to return home and be part of that sacrilege.

I'm not sure if sacrilegious hubris is what truly angered Sagarmatha and caused her to wreck revenge on her hapless victims but ever since the British first decided to conquer the world's tallest mountain, she has claimed 200 lives and a 120 of those lifeless remains are still frozen on her slopes.

(For those interested, you can read the original Outside magazine article that Jon Krakauer authored here.)

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Sunday, November 14, 2010

Овсянки / Silent Souls (2010)

This is a Russian film by director Aleksei Fedorchenko (Алексей Федорченко) which was shown on the 14th November 2010 as part of the Golden Horse Film Festival (金馬影展) held in Taipei annually. The film lends itself to comparison with a recent Taiwanese film which is also being shown at the festival Seven Days in Heaven (父後七日). Both films deal with the grieving process, although the way it is dealt with is and its cultural significance differ greatly. Silent Souls deals not only with the death of Tanya and the protagonist's father, mother and sister, but also with the death of the Meryan culture, which the protagonist sees as a necessary evil, that should be let be. Although the Finno-Ugric Meryan language had been lost, some of the traditions, like tying coloured threads onto the pubic hair of new brides and dead women and "smoking" i.e. telling someone else all about the intimacy secrets between you and your lover before their body is cremated, had been preserved by some. The protagonist had collected these cultural remnants, along with photographing the typical Meryan features, but he knows that with his death the only traces of the Meryan way of life will drift into oblivion. The Meryan customs bring comfort to the man whose wife has passed and to the protagonist when his father passes. Seven Days in Heaven, in contrast, although it also shows the traditional funeral rites, uncovers with gentle humour the artifice of these rites and how distant they hold one from the real emotions of grief. The two films on the surface seem then to work to opposite ends, the former is a melancholy eulogy for the great Meryan cultural tradition in anticipation of the imminent extinction of its memory, while the latter is a tender but satirical look at the traditional culture of Taiwanese.

With similar yearning for the past to the protagonist of this film, the notion of Irish Nationalism, which invents for itself a pre-colonial conception of Ireland which a United Ireland could hypothetically inherit, it insists that Irish cultural traditions should be resurrected, and Irish language and culture should be imposed in what is now called Northern Ireland, which would be incorporated into the Republic of Ireland. It is likely however that it was Ireland's colonizers that endowed a collective identity upon the Irish, whose concept of the world I doubt fitted into the modern concept of nations or indeed "the Irish". This in my opinion would change the nature of those traditions, reinventing them into autocratic conventions that mimic the very cultural hegemony that erradicated them in the first place. The protagonist's resigned entreaty from beyond the grave is to "let it be", to let the cultural traditions that he so painstakingly researched fall into irrelevance is moving and reminiscent of the words of Hugh in Brian Friel's Translations:

"a civilization can be imprisoned in a linguistic contour which no longer matches the landscape of ... fact. [...] We must learn those new names. [...] We must learn where we live. We must learn to make them our new home. [...] It is not the literal past, the 'facts' of history, that shape us, but images of the past embodied in language. [...] We must never cease renewing those images, because once we do, we fossilize."1This then is the element that unites the two films, the necessary evolution and dissolution of cultural rites with the passing of time. Nothing can be forcibly retained in the cultural mêlée, retaining anything by force will change its nature.

The film is beautifully shot, and the emotions behind the stolid 'expressionless' faces are intriguingly moving. There is no doubt that the film is open to a variety of interpretations and at times, given my unfamiliarity with Russia, some of the jokes were lost on me, however, there was a remarkable anti-dramatic quality to the film, with the unresolved love triangle, the raging passion of grief and the death of a culture all faced with a melancholy abandon, and acknowledged dispassionately by the characters themselves. The activity of the birds in the film could be taken as a proxy for the human emotion, when the men are silent the birds call excitedly, and just before the violent crash that concludes the film, the birds become silent.

Film Rating:

5/5

Slow moving but beautiful for that

Watch the trailer here

Film Rating:

5/5

Slow moving but beautiful for that

Watch the trailer here

Saturday, November 13, 2010

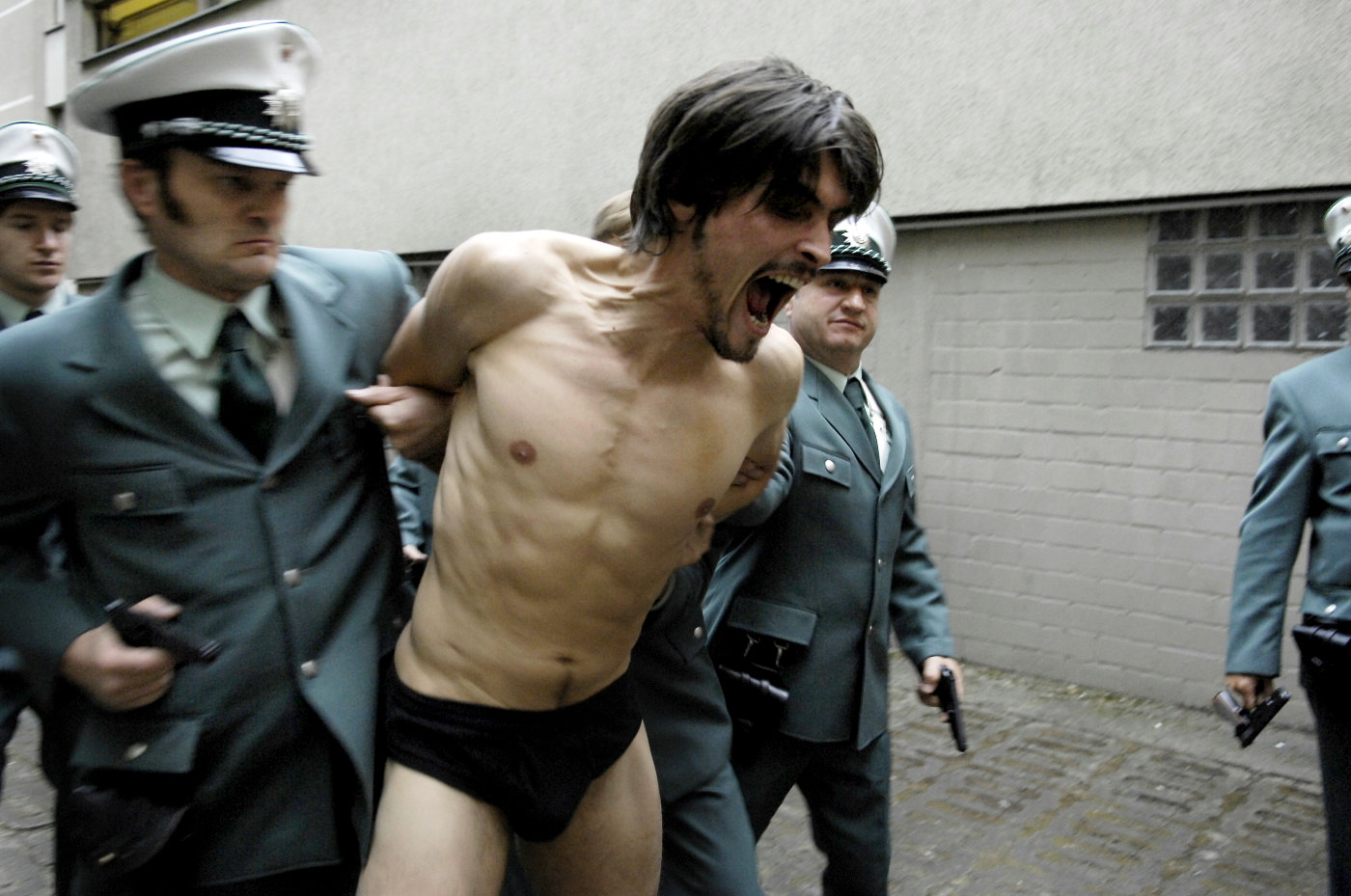

Der Baader Meinhoff Komplex (2008)

This German film, directed by Uli Edel and written by Bernd Eichinger (the same guy who wrote "Das Parfum" and "Der Untergang"), gives my generation a glimpse into 1970s Germany, where the social and cultural revolution was even more intensified than in the U.S. as the youth of Germany felt a personal responsibility to prevent fascism to rise again. At the time, the university students in Germany felt American imperialism was encroaching around the world and they felt compelled to prevent another Hitler from assuming power. One of the protestors, shirtless and brazen, shouted, "Dresden! Hiroshima! VIETNAM!" I believe this summed up their anger and frustration at the American military response to the 'red terror.' (In an earlier scene, Gudrun passionately decried America's involvement in the escalation of the Middle East conflict by supplying Israel with fighter jets and munitions.)

The film later focuses primarily on a radical faction of the disaffected youth — the Red Army Faction (RAF). This group grows increasingly violent as they find peaceful civil disobedience to be ineffective for immediate change. Their protests and minor crimes for attention soon escalate into organized bombings, robberies, kidnappings, and assassinations. This film lets you get in the shoes of the terrorists and show what was the impetus for this movement in the first place.

One of the arsonists, Gudrun Ensslin, was interviewed while in custody and she told the journalist: "This time we will put up resistance. We have a historical responsibility. People here and in America eat, eat, and shop, so they can never reflect or gain awareness, because otherwise they would have to do something. [...] I'll never resign myself to doing nothing. Never. If they shoot our people... then we are going to shoot back. [...] All over the world armed comrades are fighting. We must show our solidarity. [...] Such sacrifices have to be made. Or do you think that your theoretical masturbation will change anything?"

"What we need is a new morality. You have to draw a clear line between yourself and your enemies. Free yourself from the system and burn all bridges behind you."

-Gudrun

Trailer (in Deutsche because the English trailers don't do the movie any justice):

The movie starts off great with a string of interesting characters, great cinematography, and a gripping storyline. While the acting is superb by all the major actors and actresses, the film tends to drag a bit after the exposition. Also, the denouement also seems to be sloppy when compared to the rising action. The ending also seemed abrupt and unfinished; an epilogue might have helped with closure. Overall though, I thought the film was great and it stirred up great interest in me concerning the RAF, which I've never heard of before.

I also never knew about the disturbing fact that denazification was not complete in Germany in that many ex-Nazis assumed positions of power in Germany after the war. (source: Wikipedia — Red Army Faction).

Monday, November 1, 2010

A Whispered Life (2010) Marie-Francine Le Jalu, Gilles Sionnet

This film dealt with superfans of Japanese writer Osamu Dazai (太宰治). At first sight, given that the focus of obsession for these fans is an author and his novels, these fans might seem to transcend our expectations of the vulgarity of worshipping popstars, or cultural icons, it is soon clear, however, that this is not the case. The fans' obsession differs little from the teenage girls who scream hysterically at boybands. Throughout the course of the documentary the fans consistently glorify suicide and death, all the characters in the film were slightly repugnant in this way. Suicide in the film was ironically portrayed as another way to become eternal, similar in a way to the very egotistical act of writing or to the very concept of American Idol. The dramatic pathos of suicide is an attempt to endow their empty lives with meaning; an attempt to supercede the boundaries of life and death. I remember one of my teachers telling us about a Chinese poet who tried to launch his fame by commiting suicide after the completion of his book, in an attempt to mimic the suicide of other literary greats in Chinese literary history, like Qu Yuan (屈原) and Lao She (老舍). His plan failed because his writing was so bad, so he garnered attention by his suicide but his work was quickly forgotten. Each of the characters implied that "they were writing" and are attracted by suicide and mental illness as a way of marking their imaginary genius. This marks their lives with melancholy and depression, which they suppose to be central to the creative project when it in fact is seemingly incidental to creativity. The character in the film who writes her blog believes herself to be writing something of great value, and ties this value to depression and suicide, but what she is writing is the mundane description of common depression. The film echoed Dazai's call for "Love and Revolution", the directors went on to explain that they had interest in Dazai for the French qualities of this very call. This call rang false for me though, as this urge to mark one's life in the taking of it, is in essence a strong statement of one's belief in the world; one has to believe in something to be subsequently disappointed in it. Every one of the fans seemed to me to be no different from those desperately untalented people who attend American Idol auditions with so much self-belief, only to realize that talent is not a state of mind. The message that the documentary communicated to me, was similar to that of shows like American Idol; to embrace the ephermeral nature of life, and renounce attempts to hold onto this world beyond the bounds of death and to live averagely.

Film Rating 4/5

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)